In a bold move to revamp the educational environment, Graded has implemented a no-phone policy during school hours. The policy, which affects students, faculty, parents, and staff, dictates that all mobile devices be kept out of sight during school hours, 8:30 AM to 3:30 PM. Effective since the start of the 2024-2025 academic year, the policy that intends to foster a more focused, engaged, and cohesive school environment has sparked various reactions from the school community.

The rationale behind the no-phone policy is rooted in a growing body of research that underscores the effects of mobile phones on mental health, social interactions, and cognitive function. Superintendent Richard Boerner justifies the policy in official school communications, citing research which points to higher levels of engagement in learning and the formation of more meaningful relationships with peers and teachers when “smartphones are inaccessible.”

These arguments come in line with the recent increase in parents’ concerns about child and teenage phone use, prompted by findings that declare that smartphones are responsible for increased anxiety, depression, and mental health issues in young users. Of course, there are multiple sides to the debate, as other researchers affirm that “the phone is just a mirror that reveals the problems a child would have even without the phone.”

Whichever argument one chooses to believe, the no-phone policy is real and it is here at Graded. It’s a step forward–depending on who you ask–from the previous policy where phones were not allowed in lower and middle school, while only being restricted in classrooms for high schoolers. The administration believes that the policy gears towards the goal of “providing our students with an environment that enhances their learning, allows them to be fully present and focused,” as seen in the email from Mr. Boerner which introduced the policy. However, students aren’t the only ones affected by the new rule. Unlike many recent school phone policies, the policy encompasses teachers, faculty, staff, and even parents.

This approach intends to cultivate a unified school culture where everyone adheres to the same standards, as the adults set positive examples for the students. If this truly happens in practice is still unclear, however, as “teachers seem to continue to use their phones all the time,” 10th grader Gustavo Bartz, shares. Nonetheless, many argue that the idea in and of itself deserves merit. Ms. Laureana Piragine, high school Portuguese Teacher and Teaching and Learning Leader shares her view of the new policy on both students and teachers in the classroom environment, declaring that “First of all, it helps both teachers and students focus on what goes on in the classroom (and not outside it). […] Secondly, it drastically reduces the cognitive overload present in the never-ending multi-tasking that phones and social media impose on us.”

Parents are also asked to play a supportive role in the change by adhering to the new policy. Parents’ smartphones should be used discreetly in designated areas to set a standard for their children on campus.

Among students, reactions to the new policy have been diverse. “I understand that for the lower schoolers, this might be an important rule to enforce because they are still developing, but [students] in the high school would like to be treated as the ‘almost’ adults that we ‘almost’ are,” affirms Luisa Ansanelli, an 11th Grader. Understandably, there has been a level of frustration regarding the “loss of privileges” as students are reaching adulthood.

Furthermore, students point out the various inconveniences that arose due to the rule. In particular, juniors Bia Cohn and Madu Fernandes describe a “struggle to find my friends during breaks,” problems with getting to class on time as “the school has very few clocks around,” and having to “stop in the middle of the corridor, sit on the floor, open [their] computer, and text from there.” Betina Blay, a 10th grader, points out that “when I need to speak with my parents about private matters, I don’t feel comfortable using a school phone in the office.”

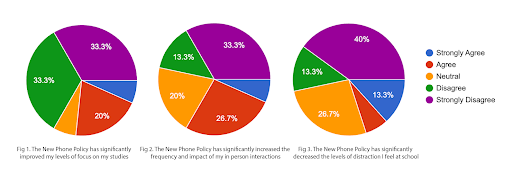

However, results from a Google Forms questionnaire conducted in September 2024, with respondents from all grade levels in the high school, suggest that the general distaste for the policy does not tell a complete story. Many students can’t deny the positive effects that the policy has had on their lives and learning. Sei Seo, 11th grader, discloses a conclusion that she herself found hard to believe: “I honestly do not want to admit it, but yes, the new phone policy has improved my focus level. When the new phone policy didn’t exist, I would often turn on my phone screen just to check if there were any notifications. When my phone was on the table I would glance at it and pointlessly pick it up! This was a huge distraction to my studies, I had to stop, check my phone, and go back to studying. As a result, the hours I spent studying in classes were a load but the quality of the study was significantly minimal. It was an extremely inefficient way of studying.” She continues by explaining what has changed after the policy’s implementation: “Yet, now that I am prohibited from using my phone, I engage enthusiastically without the phone in my sight and without the thought of checking my phone.”

In the questionnaire (shown below), 26% of students answered that they felt a significant impact on their ability to focus, and 20% described a tangible decrease in the levels of distraction they felt. João Vitor Ansanelli, a 9th grader, reveals that “the new phone policy has removed countless distractions, making me much more focused in classes and more social in breaks.” This mirrors the thoughts of sophomore Nico Della Rosa, who states that he “believe[s] that the new phone policy has made students, especially high schoolers, more social during flex and lunch.” He shares an example, that, “last year most of my friends would have preferred to play mobile games on their phone together than to actually talk to one another. Due to this new phone policy, this is no longer an option and these same people spend flex playing sports instead.”

As controversy surrounds the new policy, it is useful to look to what other institutions are acting. Is the no-phone campus unique to Graded? Anne Baldisseri, Head of School at Avenues São Paulo, shared that “Since we launched Avenues in 2018 we have had a no-phone policy for students during school hours,” stating that “[students] must leave their phones in the lockers when they arrive at school and can only use them after dismissal.” Ms. Baldisseri’s description provides insight that other international schools in the São Paulo area agree on the principle of the policy. At the same time, Ms. Baldisseri makes an important distinction that the policy does not apply to teachers, as “[Avenues’] campus is large and [faculty members] communicate on teams with one another so [they] need this ability to be able to communicate for safeguarding reasons,” a point that also applies to Graded, which has a 16.5-acre campus.

The high school principal at Chapel School was contacted but declined to comment.

As the first month back on campus comes to a close, students have raised questions and suggestions of varying levels of change surrounding the policy. Many question the necessity of enforcing the, as 11th grader Charlotte Lima remarks, “over the top” rules such as the mandatory switch to google-chat from the commonly used WhatsApp for school communication, as well as the obligatory confiscation of phones upon entering the library during students’ academic prep blocks. Nico Della Rosa shares that “I would suggest that students are allowed to use their phone during the 2:00 – 2:10 break to check their WhatsApp and emails to know what their plans are after school,” citing that “communication is much harder since you cannot check your phone during school time” to clarify such plans. Others suggest a more drastic change–11th grader Arthur Sallouti proposes a rule where “students have the freedom to use their phones between classes and during flex and lunch, and during free blocks. However, like before, if they use their phones in class and the teacher confiscates them, the same confiscation rules will apply as in the current policy.” 10th grader Beatriz Ramazotti agrees to reverting to the old policy, sharing her view that “during breaks, students should be to use their phones freely, as it is their time to unwind.” Finally, reflecting a view shared by many members of the student body, Betina Blay questions the policy’s rationale, stating that “Graded should learn to grow with technology instead of discouraging its use.”

As Graded navigates this new territory, it is clear that these changes to the role of technology will continue to have repercussions in the school community. For now, the no-phone policy stands as a significant shift in the daily routine at Graded, aiming to strike a balance between the benefits of technology and the importance of uninterrupted learning and genuine human connection. Whether this balance is achieved, has yet to be determined.

Sources:

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/27/briefing/phones-mental-health.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/17/technology/kids-smartphones-depression.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/11/technology/school-phone-bans-indiana-louisiana.html