Let’s get physical

source: Noah von Hochman (labeled for reuse)

The legendary sumo wrestler Chiyonofuji, the theme of our next print edition, was nicknamed “The Wolf” for the piercing, unnerving stare he gave his opponents. I can’t help but wonder if that helped him win, or just made him look constipated, but it’s true that society puts a lot of stock in the power of people’s eyes. History and literature are strewn with descriptions similar to Chiyonofuji’s. When an anti-Nazi police officer supervised one of Hitler’s speeches, he was supposedly “swept right off his feet” by Hitler’s “fatal hypnotizing and irresistible glare,” joining the Nazi Party the next day. Haruki Murakami, in his novel A Wild Sheep Chase, frequently refers to the antagonist’s eyes and their “arresting color.” And we all know the myth of the Cyclops, who turned savage because he couldn’t wink.

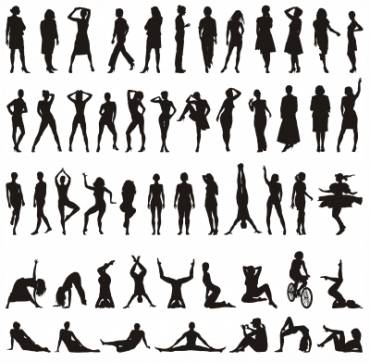

It seems kind of strange that we can get so unnerved or inspired through the movement of a few muscles. It turns out that many psychologists believe that up to fifty-five percent of our perceptions of other people come from body language. Plenty more psychologists have challenged that number, but at the very least body language is worth investigating. For one thing, why do we do it in the first place?

In a lecture, psychologist Stephen Pinker indirectly provides some answers. He cites anthropologist Alan Fiske’s three human relationship categories: dominance, communality, and reciprocity. They are all based on either evolutionary or ancient needs, and they apply only to certain people. Dominance is a relationship where one person exerts power over another; communality is a relationship between family and friends, one where we do things to be caring; and reciprocity is a more business-oriented relationship involving mutual gain. Pinker says that when these categories are messed with, awkwardness happens. For example, if an employee were to steal food off his boss’ plate, that would be inappropriate, because he would be confusing that relationship of dominance with one of communality. However, Pinker points out that this can be avoided through linguistic “negotiation.” In the rest of his lecture he talks about this in terms of euphemisms–saying one thing and meaning another is intentionally ambiguous, so social lines can be crossed. This can also be applied to body language, though. If an employee asked a boss for a raise while leaning in seductively, the employee could extend a dominance relationship into communality. It seems that in social interactions there are two different conversations happening, one verbal and one visual.

But, like any other language, body language has rules. For instance, public speakers often point or move their hands for emphasis. When you think about it, it’s pretty bizarre that adult flail their arms back and forth in front of audiences, and that’s socially acceptable. It’s a visual aid, though, that helps the audience conceptualize the facts as points in space, and not abstract ideas.

Another interesting rule to keep in mind is to avoid discordance, meaning that our body language has to be consistent. Shaking someone’s hand while facing the other direction sends two distinct social signals, and it confuses the recipient. On a more extreme note, this helps explain why psychopaths in movies are scary. A grinning, axe-wielding Jack Nicholson is more disturbing than your average mad axe-man because there’s discordance in his body language.

But there’s more to it than that. Youtube vlogger Vsauce explains in a more general way why we find things creepy. In one of his videos, he claims that a lot of creepiness comes from ambiguity. Humans have survival instincts that tell us if something is safe (like a parent) or dangerous (like a predator). When something straddles both categories in what Vsauce calls “the uncanny valley,” then it’s considered to be creepy because it doesn’t fit into either cognitive box. A picture of a person with an unnaturally wide smile freaks us out, since it is kind of familiar, but borders the unknown. Masks are creepy for the same reason–they hide the wearer’s facial expressions and make their intentions unclear. I experienced this “uncanny valley” phenomenon firsthand when I passed a child mannequin at the mall with an above-average head size. It was one of the most terrifying things I’ve ever seen, just because it wasn’t quite human.

Now, that’s not exactly body language (unless you can change head size), but there’s a common point to be made here. Issues with euphemisms, body language and the supernatural all stem from the same evolutionary process. We subconsciously rely on our animal instincts all the time to see if the people around us should be trusted or not. If we can creep people out, make strong arguments, get raises, and win wrestling matches just by playing to humanity’s primal urges and fears, then maybe we should put more stock in that side of ourselves. That’s survival 101.

Sources: jewishvirtuallibrary.org, youtube.com/vsauce, youtube.com/thersaorg, fatladysings.us

Adam is an Editor-in-Chief of The Talon. Before that he was the Features Editor, and before that he was the Assistant Features Editor. Before that, he...