From page to screen: OK, it works (sometimes)

As a voracious reader, I grew up watching my favorite books become multimillion-dollar movie franchises, long ordeals of great speculation and excitement that nearly always ended in frustration and anger. From the Chronicles of Narnia to Matilda, I’ve seen my favorite books destroyed by bad CGI, mediocre actors, and brutal plot changes again and again.

Remember Anne Hathaway’s take on Ella Enchanted? Ugh. Over time, these disappointments taught me the virtues of patience, courage, and acceptance, and the unquestionable supremacy of words over television, hence my refusal to watch the Book Thief’s latest movie version, Nancy Drew, Holes, The Giver, and any of American Girl’s adaptations.

But every rule has an exception. Baz Luhrmann’s take on Romeo + Juliet was impressive and Francis Lawrence’s Catching Fire was (unsurprisingly) infinitely better than the book. While the film adaptations that escape my wrath are rare, they do exist. On that note, I just watched Gone Girl.

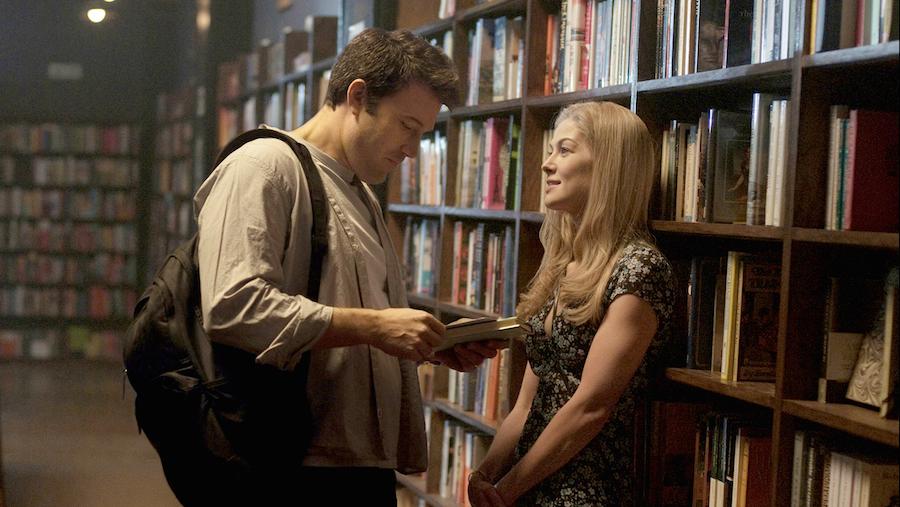

Written by Gillian Flynn, also the movie’s screenwriter, the New York Times bestseller has conjured millions of fans since its release in 2012. The novel tells the troubled story of a married couple, Nick and Amy Dunne, through Amy’s journal and Nick’s account of the events following her mysterious disappearance.

Initially, Nick and Amy seem like relatable characters, whose insecurities, relationships, and financial issues seem all too real. But as the plot thickens, the characters and events soon become tangled in this absurd web of unreality and drama (to avoid saying anything else). By the time we meet Andie, Gone Girl is no longer a portrayal of generation Y’s frustrations, but a commentary on sensationalist media, public appearance, and the complex, and often destructive, nature of marriage.

When the movie was announced, I couldn’t help but smile. Previous experience had taught me to be wary of any type of adaptation, but I was impressed by the cast and crew, and Gillian Flynn’s role as the main screenwriter came as a great relief. With Rosamund Pike as Amy and David Fincher—whose resumé includes an impressive collection of films and TV shows, from The Social Network to House of Cards—as director, the movie couldn’t possibly go wrong.

The brilliant acting, the lighting and the ominous soundtrack scored by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross (the frontman and the producer of Nine Inch Nails), David Fincher creates an overarching sense of dread, occasionally brightened by a dark joke, which lasts throughout the film, leaving you hanging on the edge of your seat. It opens with Nick pondering, “What are you thinking? How are you feeling? What have we done to each other?” and ends with him repeating those lines, adding, “What will we do?”

If you’re reading the book, finish it first. The spoilers are far too intense and will most likely ruin the reading experience (I recall choking on my gum the first time Amy shows her true colors. Now that’s what I call fun). If you’re too lazy to read it, watch the movie. The book is a fun, quick, toilet-seat read, and unless you’re desperate to meet Desi’s creepy mom, Tanner Bolt’s wife, and the few minor details the movie had to omit, David Fincher’s adaptation will do even better than the book, leaving you with a powerful, haunting, and darkly comical impression for days.

But why do most adaptations flop while some turn out much better than the original? Is it simply a question of directing and quality of production, or does the nature of the novel also play a role? After re-reading a few pages, I realized, Gone Girl was never meant to be a book. The fast-paced plot, the creepy smiles exchanged by Nick and Amy, and the dark, terrifying mood can only be successfully conveyed on the big screen. Similarly, Suzanne Collins’ YA novel Catching Fire was never able to depict the dazzling Capitol and the bleak, futuristic society of Panem quite as effectively as Francis Lawrence’s film reproduction.

Furthermore, the standards to which we hold certain books can also make us judge their picture adaptations beforehand. Was the 2007 version of Pride and Prejudice that bad? What about Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby? Trying to find a balance open-mindedness with a critical approach allows us to fully enjoy the originals and the adaptations. This applies not only to literature, but also to music, TV shows, and theatre. Gone Girl is a refreshing reminder of this fact.

MC Otani is an Editor in Chief of The Talon. Besides writing, her passions include interpretive dance, tulle, and manatees. She hopes to one day become...