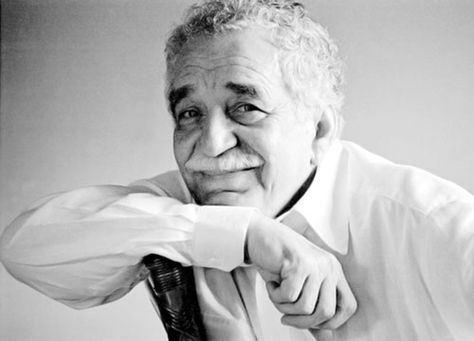

The world says goodbye to Gabo

On April 17, Nobel Prize-winning Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who familiarized the world with the literary genre magical realism, died in his home in Mexico City. He was 87 years old. García Márquez’s powerful blend of the miraculous and the ordinary, present in his series of emotionally rich novels that cover an array of social criticisms, has made him one of the most renowned and influential writers of the 20th century.

Known affectionately throughout Latin America as “Gabo,” García Márquez was a Colombian novelist, screenwriter, playwright, journalist, and memoirist, as well as a student of modernist literature and political history. Before being awarded the 1972 Neustadt International Prize for Literature and the 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature, he chose to pursue his education independently and leave law school to pursue a career in journalism. Since the early years of his work, García Márquez was known for his signature criticism of both Colombian and foreign politics. While he started out primarily as a journalist, he went on to write many lauded works of nonfiction and short stories, and is mostly known for his novels. Among his most celebrated are One Hundred Years of Solitude, The Autumn of the Patriarch, and Love in the Time of Cholera.

García Márquez’s works have achieved significant recognition and widespread commercial success, which is mostly due to his ability to characterize South American cultures and depict their social constructs through magical realism. Within his novels, novellas, and short stories, he explored relatable themes such as love, loneliness, death, and power, all of which are evident in his masterpiece One Hundred Years of Solitude. In this epic novel, García Márquez implemented his distinctive portrayal of political, social, and economic ideas that reflected the experience of an entire continent, while simultaneously involving supernatural elements in the storyline. The fictional village Macondo, which is the setting of this novel and some of his others, was mostly based off of his birth town of Arataca, and served to embody several characteristics of his home as well as the rest of South America.

Magical realism and the fusion of two habitually contrasting literary methods—the realist and the fabulist— set García Márquez apart with his depiction of the enigmatic and dull aspects of a decaying South American society. As something many people had never been exposed to before, the introduction of magical realism brought with it a new way of communicating and understanding the world to readers and writers alike. In his earlier works, reality is rationally structured with no dents in the reflection of Colombian life, but García Márquez said in retrospect “they belong to a kind of premeditated literature that offers too static and exclusive a vision of reality.” He later began experimenting with the constructs of reality by using less traditional approaches, so that “the most frightful, the most unusual things are told with a deadpan expression.”

Magical realism is sometimes notorious for dichotomizing or exoticizing, but Gárcia Márquez seems to show just the opposite. As noted by literary critic Michael Bell, “what is really at stake is a psychological suppleness which is able to inhabit unsentimentally the daytime world while remaining open to the promptings of those domains which modern culture has, by its own inner logic, necessarily marginalized or repressed.” In a literary world where storms rage on for years at a time, flowers fall from the skies, and corpses fail to decompose, the legacy of Gabo will transcend time periods and cultures, and live on.

Sources: washingtonpost.com, nytimes.com, theguardian.com

This is Paula's second year writing for The Talon, where she works as the Editor-in-Chief. Unlike some of her fellow Talonistas, she cannot think of anything...